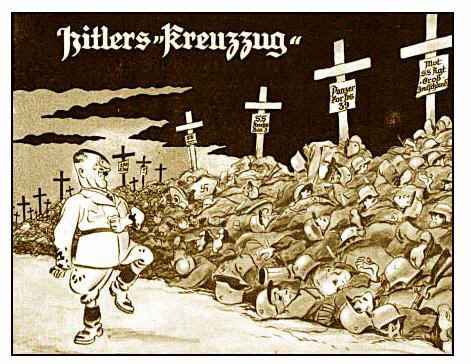

Goering: Church and Reich

We planned a separation, that is to say, the clergy were to concentrate on their own sphere and refrain from becoming involved in political matters. Owing to the fact that we had in Germany political parties with strong church leanings, considerable confusion had arisen here. That is the explanation of the fact that, because of this political opposition that at first played its role in the political field in parliament, and in election campaigns, there arose among certain of our people an antagonistic attitude toward the Church. For one must not forget that such election disputes and speeches often took place before the electors between political representatives of our Party and clergymen who represented those political parties which were more closely bound to the Church. Because of this situation and a certain animosity, it is understandable that a more rabid faction--if I may use that expression in this connection--did not forget these contentions and now, on its side, carried the struggle on again on a false level. But the Fuehrer's attitude was that the churches should be given the chance to exist and develop.

In a movement and a party which gradually had absorbed more or less the greater part of the German nation--and which now in its active political aspect had also absorbed the politically active persons of Germany--it is only natural that not all the members would be of the same opinion in every respect, despite the Leadership Principle. The tempo, the method, the attitude may be different; and in such large movements, even if they are ever so authoritatively led, certain groups form in response to certain problems. And if I were to name the group which still saw in the Church, if not a political danger, at least an undesirable institution, then I should mention above all two personages: Himmler on one side and Bormann--particularly later on much more radically than Himmler--on the other side.

This was repeatedly told to the soldiers and officers at roll call. But to the Church itself I said that it would be good if we had a clear separation. Men should pray in church and not drill there; in the barracks men should drill and not pray. In that manner, from the very beginning, I kept the Air Force free from any religious disturbances and I insured complete liberty of conscience for everyone. The situation became rapidly more critical--and I cannot really give the reasons for this--especially in the last 2 or 3 years of the war. It may have something to do with the fact that in some of the occupied territories, particularly in the Polish territory and also in the Czech territory, the clergy were strong representatives of national feeling and this led again to clashes on a political level which were then naturally carried over to religious fields. I do not know whether this was one of the reasons, but I consider it probable.

Dr Stahmer: Now, in the course of years, a large number of clergy, both from Germany and especially from the occupied territories--you yourself mentioned Poland and Czechoslovakia--were taken to concentration camps. Did you know anything about that?

The Nuremberg Tribunal Biographies

Caution: As always, these excerpts from trial testimony should not necessarily be mistaken for fact. It should be kept in mind that they are the sometimes-desperate statements of hard-pressed defendants seeking to avoid culpability and shift responsibility from charges that, should they be found guilty, can possibly be punishable by death.

Disclaimer:The Propagander!™ includes diverse and controversial materials--such as excerpts from the writings of racists and anti-Semites--so that its readers can learn the nature and extent of hate and anti-Semitic discourse. It is our sincere belief that only the informed citizen can prevail over the ignorance of Racialist "thought." Far from approving these writings, The Propagander!™ condemns racism in all of its forms and manifestations.

Source Note: The trial portion of this material, which is available in its entirety at the outstanding Avalon and Nizkor sites, is being presented here in a catagorized form for ease of study and is not meant to supplant or replace these highly recommended sources.

Fair Use Notice: This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of historical, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, environmental, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a "fair use" of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.