Goering: France

Dr Stahmer: For what reason were officers interned in France again, even after the war was over?

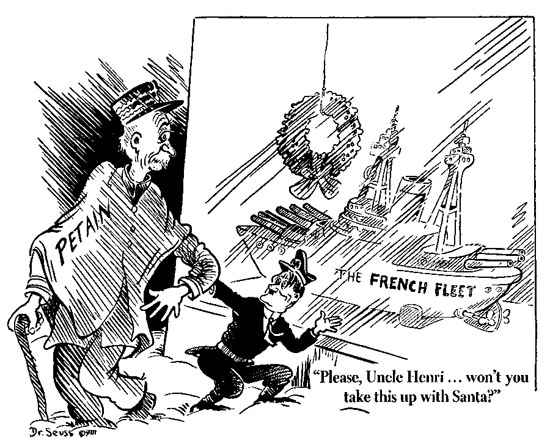

No line, no French formation, could have stopped the breakthrough of German troops to the Mediterranean. No reserves were available in England. All the available forces were in the expeditionary force which had been routed in the Belgian and Northern French area and finally at Dunkirk. In this armistice those conditions were respected for which a wish had been expressed. The Fuehrer also, apart from that, had hinted at a certain generous solution, especially in regard to the question of captured officers. When, contrary to far-reaching satisfaction which we had hoped for, and which we really got at the beginning, the resistance movement within France began to develop gradually by means of propaganda from across the Channel, and the establishment there of a new center of resistance under General de Gaulle, it was perfectly understandable, from my point of view, that French officers would offer their services as patriots.

Dr Stahmer: Can you give us specific facts to explain why the struggle in France, which was apparently carried out in a mutually honorable manner in 1940, later took on such a bitter character?

Goering: One must consider the two phases of the war with France completely separately. The first phase was the great military conflict, that is to say, the attack of the German forces against the French Army. This struggle was executed quickly. One cannot say that it was a chivalrous fight throughout, because from that period we know of several acts on the part of the French against our prisoners, which were recorded in the White Books and later presented to the International Red Cross in Geneva. But all in all, it kept within the usual bounds of a military war with the excesses that always occur here and there in such a struggle.

A war behind the front during a period of land warfare represented difficulty enough but when aerial warfare was added, entirely new possibilities and methods were developed. Night after night a large number of planes came and dropped a tremendous quantity of explosives and arms, instructions, et cetera for this resistance movement, in order to strengthen and enlarge it. The German counterintelligence succeeded, by means of aerial deception and code keys dropped by enemy planes, in getting into their hands a large part of these materials; but a sufficient amount was left which fell into the hands of the resistance movement. The atrocities committed in this connection were also widespread. As to this, documents can be submitted.

Goering: I believe that the statement which I am about to make will fulfill those conditions which Justice Jackson has requested; namely, I do not in any way deny that things happened which may be hotly debatable as far as international law is concerned. Also other things occurred which under any circumstances must be considered as excesses. I wanted only to explain how it happened, not from the point of view of international law as regards reprisals, but considering it only from the feeling of the threatened soldier, who was constantly hindered in the execution of his task, not by regular troops in open combat, but by partisans at his back.

Out of all those things which I need not go into any further, this animosity arose which led spontaneously 00 or in certain cases was ordered as a necessity in a national emergency--to these partial excesses committed here and there by the troops. One must go back to that period of stormy battles. Today, after the lapse of years, in a quiet discussion of the legal basis, these things sound very difficult and even incomprehensible. Expressions made at a bitter moment, today, without an understanding of that situation, sound quite different. It was solely my intention to depict to the Tribunal for just one moment that atmosphere in which and out of which such actions, even if they could not always be excused, would appear understandable, and in a like situation were also carried out by others.

Dr Stahmer: What measures were taken by the German occupational authorities in France to help French agriculture during the occupation?

Dr Stahmer: Document Number 141-PS is a decree of yours issued 15 November 1940 in which you effected a regulation regarding art objects brought to the Louvre. Are you familiar with this decree or shall I hand it to you?

Indeed it was my plan that this gallery should be arranged on quite different lines from those usually followed in museums. The plans for the construction of this gallery, which was to be erected as an annex to Karinhall in the big forest of the Schorfheide, and in which the art objects were to be exhibited according to their historical background and age in the proper atmosphere, were ready, only not executed because of the outbreak of war. Paintings, sculptures, tapestries, handicraft, were to be exhibited according to period. Then, when I saw the things in the Salle du Jeu de Paume and heard that the greater part were to go to Linz, that these objects which were considered to be of museum value were to serve only a minor purpose, then, I do admit, my collector's passion got the better of me; and I said that if these things were confiscated and were to remain so, I would at least like to acquire a small part of them, so that I might include them in this North German gallery to be erected by me.

In this decree, which I called a "preliminary decree" and which the Fuehrer would have had to approve, I emphasized that part of the things were to be paid for by me, and those things which were not of museum value were to be sold by auction to French or German dealers, or to whomever was present at the sale; that the proceeds of this, as far as the things were not confiscated but were paid for, was to go to the families of French war victims. I repeatedly inquired where I was to send this money and said that in collaboration with the French authorities a bank account would have to be opened. We were always referring to the opening of such an account. The amount of money was always available in my bank until the end.

In summarizing and concluding, I wish to state that according to a decree I considered these things as confiscated for the Reich. Therefore I believed myself to be justified in acquiring some of these objects, especially as I never made a secret of the fact--either to the Reich Minister for Finance or to anybody else--that these art objects of museum value, as well as the ones I previously mentioned as already in my possession, were being collected for the gallery which I described before.

Later, after I had acquired these objects, I naturally used some of them as well as some of my own for general trading with museums. In other words, if a certain museum was interested in one of those pictures and I was interested, for my gallery, in a picture which was in the possession of that museum, we would make an exchange. This exchange also took place with art dealers from. abroad. This did not concern exclusively pictures and art objects of these acquisitions, but also those which I had acquired in the open market, in Germany, Italy, or in other countries or which were earlier in my possession. At this point, I would like to add that independent of these acquisitions--and I am referring to the Salle du Jeu de Paume, where these confiscated objects were located--I, of course, had acquired works of art in the open market in France as in other countries before and after the war, or rather during the war.

I might add that usually if I came to Rome, or Florence, Paris, or Holland, as if people had known in advance that I was coming, I would always have in the shortest time a pile of written offers, from all sorts of quarters, art dealers, and private people. And even though most were not genuine, some of the things offered were interesting and good, and I acquired a number of art objects in the open market. Private persons especially made me very frequent offers in the beginning. I should like to emphasize that, especially in Paris, I was rather deceived. As soon as it was known that it was for me the price was raised 50 to 100 percent. That is all I have to say briefly and in conclusion in regard to this matter.

Dr Stahmer: Did you make provisions for the protection of French art galleries and monuments?

Goering: I should like to refer at first to the state art treasures of France, that is, those in the possession of the state museums. I did not confiscate a single object, or in any way remove anything from the state museums, with the exception of two contracts for an exchange with the Louvre on an entirely voluntary basis. I traded a statue which is known in the history of art as La Belle Allemande, a carved wood statue which originally came from Germany, for another German wood statue which I had had in my possession for many years before the war, and two pictures--an exchange such as I used to make before the war with other museums here, and as is customary among museums.

Here I can say that perhaps sometimes I issued an order which stood in contradiction to my strictly military duties, because I strongly emphasized to my fliers that the magnificent Gothic cathedrals of the French cities were, under all circumstances, to be protected and not to be attacked, even if it were a question of troop concentrations in those places; and that if attacks had to be made, precision bombing Stukas were to be used primarily. Every Frenchman who was present at the time will confirm this, that the peculiar situation arose, be it in Amiens, Rouen, Chartres or in other cities, that the cathedrals--those art monuments of such great importance and beauty were saved and purposely so, in contrast to what later happened in Germany. There was of course some broken glass in the cathedrals, caused by bomb detonations, but the most precious windows had been previously removed, thank God. As far as I remember, the small cathedral in Beauvais had fallen victim to bombing attacks on the neighboring houses, the large cathedral still is standing. The French Government repeatedly acknowledged recognition of this fact to me. I have no other comment on that point.

Goering: Colonel Veltjens was a retired colonel. He was a flier in the first World War. He then had entered business. Therefore, he was not sent there in his capacity as colonel, but as an economist. He was not only in charge of the black market in France, but also of that in Holland and Belgium. It came about in the following manner: After a certain period during the occupation, it was reported to me that various items, in which I was particularly interested for reasons of war economy, could be obtained only in the black market. It was then, for the first time, that I became familiar with the black market, that is that copper, tin, and other vital materials were still available, but that some of them lay buried in the canals of Holland, and had also been carefully hidden in other countries. However, if the necessary money were paid, these articles would come out of hiding, while, on the basis of the confiscation order, we would receive only very little of the raw materials necessary for the conduct of the war.

The unpleasant thing was that other departments, first without my knowing it--as the French Prosecution has shown here quite correctly--also tried in the same way to get the same things, in which they also were interested. The thought of now having internal competition as well was too much for me. So, then I gave Veltjens the sole authority to be the one and only office in control as far as the civilian dealers were concerned who insisted they could procure these things only in that other way, and to be the only purchasing office for these articles and, with my authority, to eliminate other offices.

The difficulty of combating the black market is the result of many factors. Afterwards, at the special request of Premier Laval, I absolutely prohibited the black market for Veltjens and his organization as well. But in spite of this it was not thereby eliminated, and the statement of the French Prosecution confirms my opinion that the black market lasted even beyond the war. And as far as I know it is again flourishing here in Germany today to the widest extent. These are symptoms which always arise during and after a war when there is on the one hand a tremendous scarcity and holding back and hiding of merchandise and on the other hand the desire to procure these things.

The Nuremberg Tribunal Biographies

Caution: As always, these excerpts from trial testimony should not necessarily be mistaken for fact. It should be kept in mind that they are the sometimes-desperate statements of hard-pressed defendants seeking to avoid culpability and shift responsibility from charges that, should they be found guilty, can possibly be punishable by death.

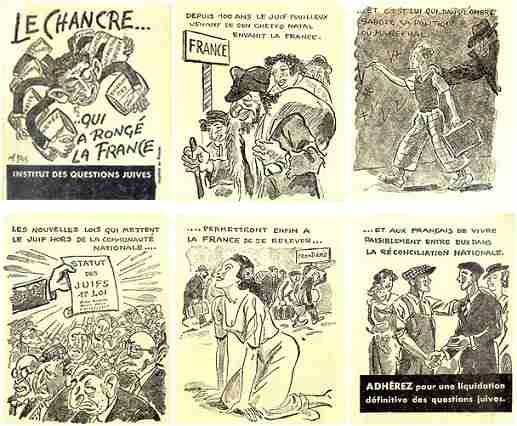

Disclaimer:The Propagander!™ includes diverse and controversial materials--such as excerpts from the writings of racists and anti-Semites--so that its readers can learn the nature and extent of hate and anti-Semitic discourse. It is our sincere belief that only the informed citizen can prevail over the ignorance of Racialist "thought." Far from approving these writings, The Propagander!™ condemns racism in all of its forms and manifestations.

Source Note: The trial portion of this material, which is available in its entirety at the outstanding Avalon and Nizkor sites, is being presented here in a catagorized form for ease of study and is not meant to supplant or replace these highly recommended sources.

Fair Use Notice: This site--The Propagander!™--may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of historical, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, environmental, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a "fair use" of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.