Goering: Barbarossa

Dr. Stahmer: To what extent did you assist in the economic and military preparation of Case Barbarossa?

Goering: As Commander-in-Chief of the Air Force I naturally took all the measures which were necessary in the purely military field for the preparation of such a campaign . . . . I took the obvious military preparations which are always necessary in connection with a new strategic deployment, and which every officer was in duty bound to carry out, and for which the officers of the Air Corps received their command from me. I do not believe that the Tribunal would be interested in the details as to how I carried out the deployment of my air fleet.

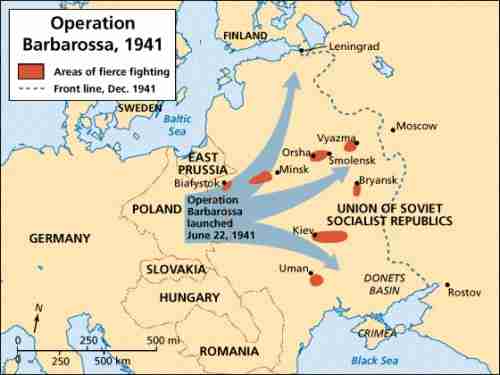

The decisive thing at the time of the first attacks was, as before, to smash the enemy air arm as the main objective. Independent of the purely military preparations, which were a matter of duty, economic preparations seemed necessary according to our experiences in the previous war with Poland, and in the war in the West; and doubly necessary in the case of Russia, for here we encountered a completely different form of economic life from that in the other countries of the Continent. Here it was a matter of state economy and state ownership; there was no private economy or private ownership worth mentioning. That I was charged with this was again a matter of course resulting from the fact that I, as Delegate for the Four-Year Plan, directed the whole economy and had to provide the necessary instructions.

The Green File has been cited repeatedly, and also here some of the quotations have been torn from their context. In order to save time I do not wish to read further passages from this Green File. That can perhaps be done when documentary evidence is given. But if I were to read the whole Green File from beginning to end, from A to Z, the Tribunal would see that this is a very useful and suitable work for armed forces which have to advance into a territory with a completely different economic structure; the Court will also realize that it could be worked out only that way.

This Green File contains much positive material, and here and there a sentence which, cited alone, as has been done, gives a false picture. It provides for everything, among other things for compensation. If an economy exists in a state, when one enters into war with that state, and if one then gains possession of that economy, it is to one's interest to carry out this economy only insofar, of course, as the interests of one's own war needs are concerned--that goes without saying. But in order to save time I shall dispense with the reading of those pages which would exonerate me considerably for, I am stating, as a whole as it is, that our making claims on the Russian state economy for German purposes, after the conquest of those territories, was just as natural and just as much a matter of duty for us as it was for Russia when she occupied German territories, but with this difference, that we did not dismantle and transport away the entire Russian economy down to the last bolt and screw, as is being done here. These are measures which result from the conduct of war. I naturally take complete responsibility for them.

1. The war can be continued further only if the entire Armed Forces can be supplied with food by Russia in the third year of war.

2. Millions of people will hereby doubtless starve if we take from this country that which is needed by us.

Were you informed of the subject of this conference with the state secretaries and of this document.

First of all the German Armed Forces would have been fed, even if there had been no war with Russia. Therefore it was not the case, as one might conclude from this, that, in order to feed the German Armed Forces, we had to attack Russia. Before the attack on Russia the German Army was fed, and it would have been fed thereafter. But if we had to march and advance into Russia it was a matter of course that the army would always and everywhere be fed from that territory. The feeding of several millions of people, that is, two or three, if I figure the entire troop deployment in Russia with all its staff, cannot possibly result in the starvation of many, many millions on the other side. It is impossible for one soldier on the one side to eat so much that on the other side there is not enough left for three times that number.

The fact is moreover that the population did not starve. However, famine had become a possibility, not because the German Army was to be fed from Russia, but because of the destruction or the sending back by the Russians of all agricultural implements, and of the entire seed stocks. It was first of all impossible to bring the harvest, which had been partly destroyed by the retreating Russian troops, in from the fields to an extent even approaching what was necessary, because of inadequate implements; and, secondly, the spring and autumn crops were greatly endangered owing to the lack of implements and seed.

If this crisis was met, it was not because the Russian troops had not destroyed or removed everything, but because Germany had to draw heavily on her own stocks. Tractors, agricultural machines, scythes, and other things had to be procured, even seed, so that for the time being the troops were not fed by the country, but food had to be sent from Germany--even straw and hay. Only through the greatest efforts of organization and administration, and in cooperation with the local population could a balance gradually be achieved in the agricultural sector, and also a surplus for the German territories.

As far as I know, famine occurred only in Leningrad, as has also been mentioned here. But Leningrad was a fortress which was being besieged. In the history of war I have until now found no evidence that the besieger generously supplies the besieged with food in order that they can resist longer; rather I know only of evidence in the history of wars that the besiegers do everything to force the surrender of the fortress by cutting off the food supply. Neither from the point of view of international law nor from the point of view of the military conduct of war were we under any obligation to provide besieged fortresses or cities with food.

Dr. Stahmer: And what part did the Air Force play in the attacks on Leningrad?

"As long as my Air Force is ready to fly into the hell of London it will be equally prepared to attack the much less defended city of Leningrad. However I lack the necessary forces, and besides you must not give me, so many tasks for my Air Force north of, the front, such as preventing reinforcements from coming over Lake Ladoga and other tasks."

Dr. Stahmer: Was confiscation by the occupying power in Russia limited to state property?

Now to the question whether only state property was confiscated; as far as I know, yes. Private property, as has been mentioned here from state documents--I can easily imagine that in the cold winter of 1941-42 German soldiers took fur shoes, felt boots, and sheep furs here and there from the population--that is possible; but by and large there was no private property, therefore it could not be confiscated. I personally can speak only of a small section, namely of the surroundings of the city of Vinnitza and the city of Vinnitza itself. When I stopped there with my special train as headquarters, I repeatedly visited the peasant huts, the villages, and the town of Vinnitza, because life there interested me. I saw such abject poverty there that I cannot possibly imagine what one could have taken.

As an insignificant but informative example I would like to mention that for empty marmalade jars, tin cans, or even empty cigar boxes or cigarette boxes, the people would offer remarkable quantities of eggs and butter because they considered these primitive articles very desirable. In this connection I would also like to emphasize that no theaters or the like were ever consciously destroyed either with my knowledge or that of any other German person. I know only the theater in Vinnitza that I visited. I saw the actors and actresses there and the ballet. The first thing I did was to get material, dresses, and all sorts of things for these people because they had nothing.

As the second example, the destruction of churches. This is also a personal experience of mine in Vinnitza. I was there when the dedication took place of the largest church, which for years had been a powder magazine, and now, under the German administration, was reinstated as a church. The clergy requested me to be present at this dedication. Everything was decorated with flowers. I declined because I do not belong to the Greek Orthodox Church. As far as the looting of stores was concerned, I could see only one store in Vinnitza that was completely empty.

Mr. Justice Jackson: Now, I want to call your attention to the fruits of this system. You, as I understand it, were informed in 1940 of an impending attack by the German Army on Soviet Russia?

Goering: I have explained just how far I was informed of these matters.

Mr. Justice Jackson: You believed an attack not only to be unnecessary, but also to be unwise from the point of view of Germany itself?

Goering: At that particular time I was of the opinion that this attack should be postponed in order to carry through other tasks which I considered more important.

Mr. Justice Jackson: You did not see any military necessity for an attack at that time, even from the point of view of Germany?

Goering: Naturally, I was fully aware of Russia's efforts in the deployment of her forces, but I hoped first to put into effect the other strategic measures, described by me, to improve Germany's position. I thought that the time required for these would ward off the critical moment. I well knew, of course, that this critical moment for Germany might come at any time after that.

Goering: I personally believed that at that time the danger had not yet reached its climax, and therefore the attack might not yet be necessary. But that was my personal view.

Mr. Justice Jackson: And you were the Number 2 man at that time in all Germany?

Goering: It has nothing to do with my being second in importance. There were two conflicting points of view as regards strategy. The Fuehrer, the Number 1 man, saw one danger, and I, as the Number 2 man, if you wish to express it so, wanted to carry out another strategic measure. If I had imposed my will every time, then I would probably have become the Number 1 man. But since the Number 1 man was of a different opinion, and I was only the Number 2 man, his opinion naturally prevailed.

Mr. Justice Jackson: I have understood from your testimony--and I think you can answer this "yes" or "no," and I would greatly appreciate it if you would--I have understood from your testimony that you were opposed, and told the Fuehrer that you were opposed, to an attack upon Russia at that time. Am I right or wrong?

Goering: That is correct.

Mr. Justice Jackson: Now, you were opposed to it because you thought that it was a dangerous move for Germany to make; is that correct?

Goering: Yes, I was of the opinion that the moment--and I repeat this again--had not come for this undertaking, and that measures should be taken which were more expedient as far as Germany was concerned.

Mr. Justice Jackson: And yet, because of the Fuehrer system, as I understand you, you could give no warning to the German people; you could bring no pressure of any kind to bear to prevent that step, and you could not even resign to protect your own place in history.

Goering: These are several questions at once. I should like to answer the first one.

Mr. Justice Jackson: Separate them, if you wish.

Goering: The first question was, I believe, whether I took the opportunity to tell the German people about this danger. I had no occasion to do this. We were at war, and such differences of opinion, as far as strategy was concerned, could not be brought before the public forum during war. I believe that never has happened in world history.

Secondly, as far as my resignation is concerned, I do not wish even to discuss that, for during the war I was an officer, a soldier, and I was not concerned with whether I shared an opinion or not. I had merely to serve my country as a soldier.

Thirdly, I was not the man to forsake someone, to whom I had given my oath of loyalty, every time he was not of my way of thinking. If that had been the case there would have been no need to bind myself to him from the beginning. It never occurred to me to leave the Fuehrer.

Goering: The German people did not know about the declaration of war against Russia until after the war with Russia had started. The German people, therefore, had nothing to do with this. The German people were not asked; they were told of the fact and of the necessity for it.

Mr. Justice Jackson: At what time did you know that the war, as regards achieving the objectives that you had in mind, was a lost war?

Goering: It is extremely difficult to say. At any rate, according to my conviction, relatively late--I mean, it was only towards the end that I became convinced that the war was lost. Up till then I had always thought and hoped that it would come to a stalemate.

Mr. Justice Jackson: Well, in November 1941 the offensive in Russia broke down?

Goering: That is not at all correct. We had reverses because of weather conditions, or rather, the goal which we had set was not reached. The push of 1942 proved well enough that there was no question of a military collapse. Some corps, which had pushed forward, were merely thrown back, and some were withdrawn. The totally unexpected early frost that set in was the cause of this.

Mr. Justice Jackson: You said, "relatively late." The expression that you used does not tell me anything, because I do not know what you regard as relatively late. Will you fix in terms, either of events or time, when it was that the conviction came to you that the war was lost?

Mr. Justice Jackson: Now, will you fix that by date; you told us when it was by events.

Goering: I just said January 1945; middle, or end of January 1945. After that there was no more hope.

Mr. Justice Jackson: Do you want it understood that, as a military man, you did not realize until January of 1945 that Germany could not be successful in the war?

Goering: As I have already said, we must draw a sharp distinction between two possibilities: First, the successful conclusion of a war, and second, a war which ends by neither side being the victor. As regards a successful outcome, the moment when it was realized that that was no longer possible was much earlier, whereas the realization of the fact that defeat would set in did not come until the time I have just mentioned.

Goering: Of course, a successful termination of a war can only be considered successful if I either conquer the enemy or, through negotiations with the enemy, come to a conclusion that guarantees me success. That is what I call a successful termination. I call it a draw, when I come to terms with the enemy. This does not bring me the success which victory would have brought but, on the other hand, it precludes a defeat. This is a conclusion without victors or vanquished.

Mr. Justice Jackson: But you knew that it was Hitler's policy never to negotiate and you knew that as long as he was the head of the Government the enemy would not negotiate with Germany, did you not?

Goering: I knew that enemy propaganda emphasized that under no circumstances would there be negotiations with Hitler. That Hitler did not want to, negotiate under any circumstances, I also knew, but not in this connection. Hitler wanted to negotiate if there were some prospect of results; but he was absolutely opposed to hopeless and futile negotiations. Because of the declaration of the enemy in the West after the landing in Africa, as far as I remember, that under no circumstances would they negotiate with Germany but would force on her unconditional surrender, Germany's resistance was stiffened to the utmost and measures had to be taken accordingly. If I have no chance of concluding a war through negotiations, then it is useless to negotiate, and I must strain every nerve to bring about a change by a call to arms.

1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 87, Hermann Goering's cross-examination by the prosecution continues.

General Rudenko: Let us now pass to the next set of questions. When exactly did you start the working out of the plan of action for the use of the German Luftwaffe against the Soviet Union in connection with Case Barbarossa?

Goering: The deployment of the Luftwaffe for Case Barbarossa was worked out by my general staff, after the first directive of the Fuehrer's, that is, after the November directive.

General Rudenko: In 1940?

Goering: In 1940. But I would add that I had already considered making preparations not only in anticipation of a possible threat from Russia, but from all those countries which were not already involved in the war, but which might eventually be drawn in.

General Rudenko: All right. It was in November 1940, when Germany was preparing to attack Russia? Plans were already being prepared for this attack with your participation?

Goering: The other day I explained exactly, that at the time a plan for dealing with the political situation and the potential threat from Russia had been worked out.

Once more I say, in November 1940, more than half a year before the attack on the Soviet Union, plans were already prepared, with your participation, for the attack on the Soviet Union. Can you reply to this briefly?

Goering: Yes, but not in the sense in which you are presenting it.

General Rudenko: It seems to me that I have put the question quite clearly, and there is no ambiguity here at all. How much time did it take to prepare Case Barbarossa?

Goering: In which sector, air, land, or sea?

General Rudenko: If you are acquainted with all phases of the plan, that is concerning the Air Force, the Army and the Navy, then I would like you to answer for all phases of Case Barbarossa.

Goering: Generally speaking, I can only answer for the air, where it took a comparatively short time.

General Rudenko: If you please, just how long did it take to prepare Case Barbarossa?

General Rudenko: Thus, you admit that the attack on the Soviet Union was planned several months in advance of the attack itself, and that you, as chief of German Air Force and Reich Marshal, participated directly in the preparation of the attack.

Goering: May I divide your numerous questions. Firstly, that was not several months ...

General Rudenko: There were not too many questions asked at once. It was only one question. You have admitted that in November 1940 Case Barbarossa was prepared and developed for the Air Force. I ask you in your capacity as Commander-in-Chief of the German Luftwaffe.

Göing: That is right.

General Rudenko: You have answered already the first part of my question. Now the following part: You admit that as chief of the German Air Force and Reich Marshal you participated in preparations for the attack on the Soviet Union?

Goering: I once more repeat that I prepared for the possibility of an attack, mainly because of Hitler's assumption that Soviet Russia was adopting a dangerous attitude. In the beginning the certainty of an attack was not discussed, and that is stated clearly in the directive of November 1940. Secondly, I want to emphasize that my position as Reich Marshal is of no importance here. That is a title and a rank.

General Rudenko: But you do not deny--rather, you agree--that the plan was already prepared in November 1940?

Göing: Yes.

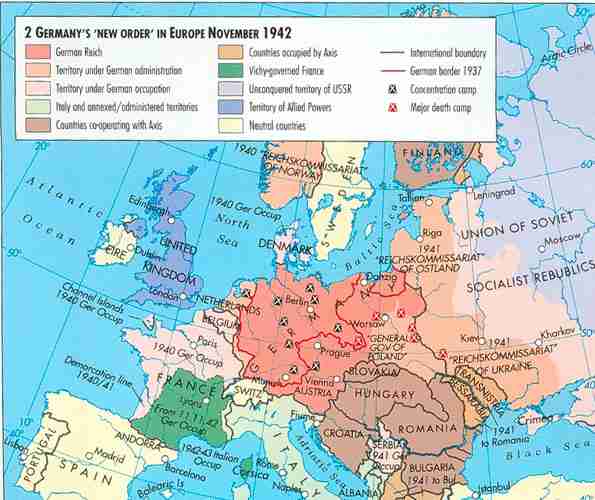

General Rudenko: It appears to me that the question has already been covered in such detail before the Tribunal that we need not talk too much about Case Barbarossa, which is quite clear. I shall go on to the next question: Do you admit that the objectives of the war against the Soviet Union consisted of invading and seizing Soviet territory up to the Ural Mountains and joining it to the German Reich, including the Baltic territories, the Crimea, the Caucasus; also the subjugation by Germany of the Ukraine, of Byelorussia, and of other regions of the Soviet Union? Do you admit that such were the objectives of that plan?

Goering: That I certainly do not admit.

Goering: I can remember the document exactly, and I have a fair recollection of the discussion at the conference. I said the first time that this document, as recorded by Bormann, appears to me extremely exaggerated as far as the demands are concerned. At any rate, at the beginning of the war, such demands were not discussed; nor had they been discussed previously.

General Rudenko: But you do admit that there are minutes of such a conference?

Goering: I admit it because I have seen them. It was a document prepared by Bormann.

General Rudenko: You also admit that according to the minutes of this meeting, you participated in that conference.

Goering: I was present at that conference, and for that reason I question the record.

General Rudenko: Do you remember that in those minutes the tasks were formulated which were in connection with developing conditions? I shall remind you of various parts of the minutes. It is not necessary to read them in full.

Goering: May I ask to be shown a copy of that record.

General Rudenko: You would like a copy of the minutes of the meeting?

Goering: I ask to have it.

General Rudenko: If you please. Would you like to read the document?

Goering: No, only where you are going to quote it.

General Rudenko: Page 2, second paragraph, Point 2, about the Crimea: "We emphasize" -- can you find the place? Do you have it?

Goering: Just a moment, I have not found it yet. Yes, I have it.

General Rudenko: "We emphasize"--states this Point 2--"that we are bringing freedom to the Crimea. The Crimea must be freed of all foreigners and populated by the Germans. Also, Austrian Galicia will become a province of the German Reich." Have you found the place?

Goering: Yes.

General Rudenko: "A province of the Reich," it says.

Goering: Yes.

General Rudenko: I want to draw your attention to the end of the minutes. It says here: "The Fuehrer stresses the fact that the whole of the Baltic States must become Reich territory." Have you found the place, "The Fuehrer stresses the fact"?

Goering: You mean the very last bit?

General Rudenko: That is right.

Goering: "Finally, it is ordered..."?

General Rudenko: A little higher up.

Goering: "The Fuehrer stresses..."?

"The Fuehrer, furthermore, stresses that the Volga region also must become Reich territory, as well as the Baku Province, which must become a military colony of the Reich. Eastern Karelia is claimed by the Finns. The peninsula Kola, however, because of the large supplies of nickel, should become German territory. Great caution must be exercised in the incorporation of Finland as a federal state. The Finns want the surrounding region of Leningrad. The Fuehrer will level Leningrad to the ground and give it to the Finns afterwards."

Have you not found the place where it mentions Leningrad and Finland?

Goering: Yes.

General Rudenko: These are the minutes of the conference at which you were present on the 16th of July 1941, 3 weeks after Germany attacked the Soviet Union. You do not deny that such minutes exist, do you? It is Document Number L-221.

Goering: Just a moment, you are mistaken in the date. You said 3 days; that is not correct.

General Rudenko: Three weeks, not 3 days.

Goering: Oh, 3 weeks; I see.

General Rudenko: Three weeks after Germany attacked the Soviet Union on the 22d of June, and the conference took place at Hitler's headquarters on the 16th of July at 1500 hours, I think. Is it correct that such a conference took place?

Goering: That is quite right. I have said so all along, but the record of this is not right.

General Rudenko: And who took the minutes of the meeting?

Goering: Bormann.

Goering: In this record Bormann has exaggerated. The Volga territory was not discussed. As far as the Crimea is concerned, it is correct, that the Fuehrer ...

General Rudenko: Well, let us be a little more precise. Germany wanted the Crimea to become a Reich territory, correct?

Goering: The Fuehrer wanted the Crimea, yes, but that was an aim fixed before the war. The same applies to the three Baltic States, which had previously been taken by Russia. They, too, were to go back to Germany.

General Rudenko: Pardon me. You say that the question of the Crimea arose even before the war, that is, the question of acquiring the Crimea for the Reich. How long before the war was that?

Goering: No, before the war the Fuehrer had not discussed territorial aims with us, or, rather which territories he had in mind. At that time, if you read the record, I myself considered the question premature, and I confined myself to more practical matters during that conference.

General Rudenko: I would like to be still more precise. You state that with regard to the Crimea, there was some question about making the Crimea Reich territory.

Goering: Yes, that was discussed during that conference.

General Rudenko: All right, with regard to the Baltic provinces, there was talk about those, too?

Goering: Yes.

General Rudenko: All right. With regard to the Caucasus, there was talk about annexing the Caucasus also?

Goering: It was never a question of its becoming German. We merely spoke about very strong German economic influence in that sphere.

General Rudenko: So the Caucasus was to become a concession of the Reich?

Goering: Just to what degree obviously could not be discussed until after a victorious war. You can see from the record what a mad thing it is to discuss a few days after a war has broken out the things recorded here by Bormann, when nobody knows what the outcome of that war will be and what the possibilities are.

General Rudenko: Therefore by exaggeration you mean that the Volga territory for instance was not discussed.

Goering: The exaggeration lies in the fact that at that time things were discussed which could not be usefully discussed at all. At the most one might have talked about territory which one occupied, and its administration.

General Rudenko: We are now trying to establish the facts, namely, that those questions had been discussed, and these questions came up at the conference. You do not deny that, do you?

Goering: There had been some discussion, yes, but not as recorded in these minutes.

General Rudenko: I would like to draw just one conclusion. The facts bear witness that even before this conference, aims to annex foreign territories had been fixed in accordance with the plan prepared months ago. That is correct, is it not?

Goering: Yes that is correct, but I would like to emphasize that in these minutes I steered away from these endless discussions, and here the text reads:

"The Reich Marshal countered this, that is, the lengthy discussion of all these things, by stressing the main points which were of vital importance to us, such as, the securing of food supplies to the extent necessary for economy, securing of roads, et cetera."

I just wanted to reduce the whole thing to a practical basis.

General Rudenko: Just so. You have contradicted yourself, inasmuch as in your opinion, the most important thing was the food supply. All the other things could follow later. It says so in the minutes. Your contradiction does not lie in your objection to the plan itself but in the sequence of its execution. First of all you wanted food and later territory. Is that correct?

Goering: No, it is exactly as I have read it out, and there is no sequence of aims. There is no secret.

General Rudenko: Please read it once more and tell me just where you disagreed.

Goering:

"After the lengthy discussion about persons and matters concerning annexation, et cetera, opposing this, the Reich Marshal stressed the main points which might be the decisive factors for us: Securing of food supplies to the extent necessary for economy, securing of roads, et cetera--communications."

At the time I mentioned railways, et cetera, that is, I wanted to bring this extravagant talk--such as might take place in the first flush of victory--back to the purely practical things which must be done.

General Rudenko: It is understandable that the securing of food supplies plays an important part. However, the objection you just gave does not mean that you objected to the annexation of the Crimea or the annexation of other regions, is that not correct?

Goering: If you spoke German, then, from the sentence which says, "opposing that, the Reich Marshal emphasized..." you would understand everything that is implied. In other words, I did not say here, "I protest against the annexation of the Crimea," or, "I protest against the annexation of the Baltic States." I had no reason to do so. Had we been victorious, then after the signing of peace we would in any case have decided how far annexation would serve our purpose. At the moment we had not finished the war, we had not won the war yet, and consequently I personally confined myself to practical problems.

General Rudenko: I understand you. In that case, you considered the annexation of these regions a step to come later. As you said yourself, after the war was won you would have seized these provinces and annexed them. In principle you have not protested.

Goering: Not in principle. As an old hunter, I acted according to the principle of not dividing the bear's skin before the bear was shot.

General Rudenko: I understand. And the bear's skin should be divided only when the territories were seized completely, is that correct?

Goering: Just what to do with the skin could be decided definitely only after the bear was shot.

General Rudenko: Luckily, this did not happen.

Goering: Luckily for you.

General Rudenko: And so, summing this up on the basis of the replies which you gave to my question, it has become quite clear, and I think you will agree, that the war aims were aggressive.

Goering: The one and only decisive war aim was to eliminate the danger that Russia represented to Germany.

General Rudenko: And to seize the Russian territories.

Goering: I have tried repeatedly to make this point clear, namely, that before the war started this was not discussed. The answer is that the Fuehrer saw in the attitude of Russia, and in the lining up of troops on our frontier, a mortal threat to Germany, and he wanted to eliminate that threat. He felt that to be his duty. What might have been done in peace, after a victorious war, is quite another question, which at that time was not discussed in any way. But to reply to your question, by that I do not mean to say that after a victorious war in the East we would have had no thoughts of annexation.

General Rudenko: I do not wish to occupy the time of the Court in returning to the question of the so-called preventive war, but nevertheless, since you touched on the subject, I should like to ask you the following: You remember the testimony of Field Marshal Milch, who stated that neither Goering nor he wanted war with Russia. Do you remember that testimony of your witness, Field Marshal Milch?

Goering: Yes, perfectly.

General Rudenko: You do remember. In that case why did you not want war with Russia, when you saw the so-called Russian threat?

Goering: Firstly, I have said already that it was the Fuehrer who saw the danger to be so great and so imminent. Secondly, in connection with the question put by my counsel, I stated clearly and exactly the reasons why I believed that the danger had not yet become so imminent, and that we should take other preparatory measures first. That was my firm conviction.

General Rudenko: But you do not deny the testimony of your witness Milch?

General Rudenko: On the basis of your replies to questions during several sessions, it appears there was no country on earth which you did not regard as a threat.

Goering: Most of the other countries did not represent a danger to Germany, but I personally, from 1933 on, always saw in Russia the greatest threat.

General Rudenko: Well, of course, by "the other countries" you mean your allies, is that right?

Goering: No, I am thinking of most of the other countries. If you ask me again I would say that the danger to Germany lay, in my opinion, in Russia's drive towards the West. Naturally, I also saw a certain danger in the two western countries, England and France, and in this connection, in the event of Germany being involved in a war, I regarded the United States to be a threat as well. As far as the other countries were concerned, I did not consider them to be a direct threat to Germany. In the case of the small countries, they would only constitute a direct threat, if they were used by the large countries, as bases in a war against Germany.

General Rudenko: Naturally the small countries did not represent the same threat because Germany already occupied them. That has often enough been established by the Tribunal.

Goering: No, a small country as such does not represent a threat, but if another large country uses the small one against me, then the small country too can become a danger.

General Rudenko: I do not want to discuss the thing further as it does not relate to the question. The basic question here is Germany's intentions with regard to the territory of the Soviet Union, and to that you have already answered quite affirmatively and decisively. So I will not ask you any more questions on this subject.

The Nuremberg Tribunal Biographies

Caution: As always, these excerpts from trial testimony should not necessarily be mistaken for fact. It should be kept in mind that they are the sometimes-desperate statements of hard-pressed defendants seeking to avoid culpability and shift responsibility from charges that, should they be found guilty, can possibly be punishable by death.

Disclaimer:The Propagander!™ includes diverse and controversial materials--such as excerpts from the writings of racists and anti-Semites--so that its readers can learn the nature and extent of hate and anti-Semitic discourse. It is our sincere belief that only the informed citizen can prevail over the ignorance of Racialist "thought." Far from approving these writings, The Propagander!™ condemns racism in all of its forms and manifestations.

Source Note: The trial portion of this material, which is available in its entirety at the outstanding Avalon and Nizkor sites, is being presented here in a catagorized form for ease of study and is not meant to supplant or replace these highly recommended sources.

Fair Use Notice: This site--The Propagander!™--may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of historical, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, environmental, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a "fair use" of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.