Goering: The Anschluss with Austria

Dr Stahmer: Before that, the Anschluss of Austria with Germany had taken place. What reasons did Hitler have for that decision, and to what extent did you play a part in those measures?

This statement by the representatives of the Austrian-German people that they wanted to be a part of Germany in the future was changed by the peace treaty of St. Germain and prohibited by the dictate of the victorious nations. Neither for myself nor for any other German was that of importance. The moment and the basic conditions had of course to be created for a union of the two brother nations of purely German blood and origin to take place. When we came to power, as I have said before, this was naturally an integral part of German policy. The assurances that Hitler gave at that time regarding the sovereignty of Austria were no deception; they were meant seriously.

Thus there resulted that tension, first in Austria itself, which has repeatedly been mentioned by the Prosecution in its charges. This tension was bound to come because the National Socialists took the idea of the Anschluss with Germany more seriously than the Government did. This resulted in political strife between the two. That we were on the side of the National Socialists as far as our sympathies were concerned is obvious, particularly as the Party in Austria was severely persecuted. Many were put into camps, which were just like concentration camps but had different names.

He regretted the death of Dollfuss very much because politically that meant a very serious situation as far as the National Socialists were concerned, and particularly with regard to Italy. Italy mobilized five divisions at that time and sent them to the Brenner Pass. The Fuehrer desired an appeasement which would be quick and as sweeping in its effect as possible. That was the reason why he asked Herr von Papen to go as an extraordinary ambassador to Vienna and to work for an easing of the atmosphere as quickly as possible. One must not forget the somewhat absurd situation which had developed in the course of years, namely, that a purely German country such as Austria was not most strongly influenced in governmental matters by the German Reich but by the Italian Government. I remember that statement of Mr. Churchill's, that Austria was practically an affiliate of Italy.

I suggested to him at that time, in view of the somewhat vague offer regarding Austria made by English-French circles, to try and find out who was behind this offer and whether both governments were willing to come to an agreement in regard to this point and to give assurances to the effect that this would be considered an internal German affair, and not some vague assurances of general co-operation, et cetera. My suspicions proved right; we could not get any definite assurances. Under those circumstances, it was more expedient for us to prevent Italy being the main opponent to the Anschluss by not joining in any sanctions against her.

Then came the Berchtesgaden agreement. I was not present at this. I did not even consent to this agreement, because I opposed any definite statement that lengthened this period of indecision; for me the complete union of all Germans was the only conceivable solution.

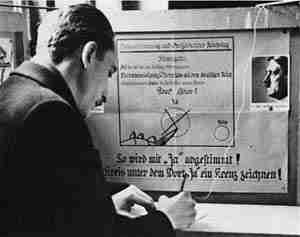

We opposed that. First of all a member of the Austrian Government who was at that moment in Germany, General von Glaise-Horstenau, was flown to Vienna in order to make clear to Schuschnigg or Seyss-Inquart--who, since Berchtesgaden, was in Schuschnigg's Cabinet--that Germany would never tolerate this provocation. At the same time troops which were stationed near the Austrian border were on the alert. That was on Friday, I believe, the 11th.

The only thing--and I do not say this because it is important as far as my responsibility is concerned--which I did not bring about personally, since I did not know the persons involved, but which has been brought forward by the Prosecution in the last few days, was the following: I sent through a list of ministers, that is to say, I named those persons who would be considered by us desirable as members of an Austrian Government for the time being. I knew Seyss-Inquart, and it was clear to me from the very beginning that he should get the Chancellorship. Then I named Ernst Kaltenbrunner for Security. I did not know Kaltenbrunner, and that is one of the two instances where the Fuehrer took a hand by giving me a few names.

For already plans had again appeared in which the Fuehrer only, as the head of the German Reich, should be simultaneously the head of German Austria; there would otherwise be a separation. That I considered intolerable. The hour had come and we should make the best use of it. In the conversation which I had with Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop, who was in London at that time, I pointed out that the ultimatum had not been presented by us but by Seyss-Inquart. That was absolutely true de jure; de facto, of course it was my wish. But this telephone conversation was being listened to by the English, and I had to conduct a diplomatic conversation, and I have never heard yet that diplomats in such cases say how matters are de facto; rather they always stress how they are de jure. And why should I make a possible exception here?

Dr Stahmer: I have had handed to you a record of that conversation. It has been put in by the Prosecution. One part of it has not been read into the record yet, but you have given its contents. Would you please look at it?

Now I come to the decisive part concerning the entry of the troops. That was the second point where the Fuehrer interfered and we were not of the same opinion. The Fuehrer wanted the reasons for the march into Austria to be a request by the new Government of Seyss-Inquart, that is the government desired by us--that they should ask for the troops in order to maintain order in the country. I was against this, not against the march into Austria--I was for the march under all circumstances--against only the reasons to be given. Here there was a difference of opinion.

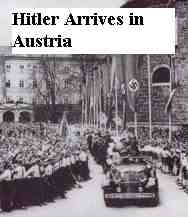

I should like to emphasize that at that time Mussolini's attitude to the Austrian question had not yet crystallized, although I had worked on him the year before to that end. The Italians were still looking with longing eyes at eastern Tyrol. The five divisions along the Brenner Pass I had not forgotten. The Hungarians talked too much about the Burgenland. The Yugoslavs once mentioned something about Carinthia, but I believe that I made it clear to them at the time that that was absurd. So to prevent the fulfillment of these hopes once and for all, which might easily happen in such circumstances, I very definitely wanted the German troops to march into Austria proclaiming: "The Anschluss has taken place; Austria is a part of Germany and therefore in its entirety automatically and completely under the protection of the German Reich and its Armed Forces."

Mussolini's consent did not come until 11:30 at night. It is well known what a relief that was for the Fuehrer. In the evening of the same day, after everything had become clear, and the outcome could be seen in advance, I went to the Flieger Club, where I had been invited several weeks before, to a ball. I mention this because here that too has been described as a deceptive maneuver. But that invitation had been sent out, I believe, even before the Berchtesgaden conference took place. There I met almost all the diplomats. I immediately took Sir Neville Henderson, the British Ambassador, aside. I spoke to him for 2 hours and gave him all the reasons and explained everything, and also asked him to tell me--the same question which I later asked Ribbentrop--what nation in the whole world was damaged in any way by our union with Austria? From whom had we taken anything, and whom had we harmed? I said that this was an absolute restitution, that both parts had belonged together in the German Empire for centuries and that they had been separated only because of political developments, the later monarchy and Austria's secession.

In this connection I want to stress two points in concluding: If Mr. Messersmith says in his long affidavit that before the Anschluss I had made various visits to Yugoslavia and Hungary in order to win over both these nations for the Anschluss, and that I had promised to Yugoslavia a part of Carinthia, I can only say in answer to these statements that I do not understand them at all. My visits in Yugoslavia and the other Balkan countries were designed to improve relations, particularly trade relations, which were very important to me with respect to the Four-Year Plan. If at any time Yugoslavia had demanded one single village in Carinthia, I would have said that I would not even answer such a point, because, if any country is. German to the core, it was and is Carinthia.

Dr Stahmer: On the evening before the march of the troops into Austria you also had a conversation with Dr. Mastny, the Czechoslovak Ambassador. On this occasion you are supposed to, have given a declaration on your word of honor. What about that conversation?

Goering: I am especially grateful that I can at last make a clear statement about this "word of honor," which has been mentioned so often during the last months and which has been so incriminating for me. I mentioned that on that evening almost all the diplomats were present at that ball. After I had spoken to Sir Neville Henderson and returned to the ballroom, the Czechoslovak Ambassador, Dr. Mastny, came to me, very excited and trembling, and asked me what was happening that night and whether we intended to march into Czechoslovakia also. I gave him a short explanation and said, "No, it is only a question of the Anschluss of Austria; it has absolutely nothing to do with your country, especially if you keep out of things altogether." He thanked me and went, apparently, to the telephone.

But after a short time he came back even more excited, and I had the impression that in his excitement he could hardly understand me. I said to him then in the presence of others: "Your Excellency, listen carefully. I give you my personal word of honor that this is a question of the Anschluss of Austria only, and that not a single German soldier will come anywhere near the Czechoslovak border. See to it that there is no mobilization on the part of Czechoslovakia which might lead to difficulties." He then agreed. At no time did I say to him, "I give you my word of honor that we never want to have anything to do with Czechoslovakia for all time."

The Nuremberg Tribunal Biographies

Caution: As always, these excerpts from trial testimony should not necessarily be mistaken for fact. It should be kept in mind that they are the sometimes-desperate statements of hard-pressed defendants seeking to avoid culpability and shift responsibility from charges that, should they be found guilty, can possibly be punishable by death.

Disclaimer:The Propagander!™ includes diverse and controversial materials--such as excerpts from the writings of racists and anti-Semites--so that its readers can learn the nature and extent of hate and anti-Semitic discourse. It is our sincere belief that only the informed citizen can prevail over the ignorance of Racialist "thought." Far from approving these writings, The Propagander!™ condemns racism in all of its forms and manifestations.

Source Note: The trial portion of this material, which is available in its entirety at the outstanding Avalon and Nizkor sites, is being presented here in a catagorized form for ease of study and is not meant to supplant or replace these highly recommended sources.

Fair Use Notice: This site may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of historical, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, environmental, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a "fair use" of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.