Goering: Luftwaffe Bombing

Dr Stahmer: During the last days we have heard here repeatedly about the aerial attacks on Warsaw, Coventry, and Rotterdam. Were these attacks carried out beyond military necessity?

Goering: The witnesses, and especially Field Marshal Kesselring, have reported about part of that. But these statements made me realize once more, which is of course natural, how a commander of an army, an army group or an air fleet really views only a certain sector. As Commander-in-Chief of the Air Force, however, I am in a position to view the whole picture, since I, after all, was the man responsible for issuing orders, and according to my orders and my point of view the chiefs of the fleets received their instructions and directives as to what they had to do.

The second main target, which was however to be attacked only to a slight extent on the first day, or with the first main blow, were railroad junctions of first importance for the marshaling of larger troop units. I would point out that shortly before the last and decisive attack on Warsaw, an air attack, about which I will speak in a minute, the French military attaché in Poland sent a report to his government which we are in a position to submit here, which we found later in Paris, from which it can be seen that even this opponent declared that the German Air Force, he had to admit, had attacked exclusively military targets in Poland, "exclusively" particularly emphasized.

Secondly, when the commanding officer persisted in his stand, we urged the evacuation of the civilian population before the bombing. When a radio message was received that the commanding officer wanted to send a truce emissary we agreed, but waited for him in vain. But then we demanded that at least the diplomatic corps and all neutrals should leave Warsaw on a road designated by us, which in fact was done. Then, after it was clearly stated in the last appeal that we would now be forced to make a heavy attack on the city if no surrender took place, we proceeded to attack first the forts, then the batteries erected within the city and the troops. That was the attack on Warsaw.

First it was surrounded by Dutch troops. Everything hinged on the fact that the railroad bridge and the road bridge, which were next to each other, should under all circumstances fall into our hands without being destroyed, because then only would the last backdoor to the Dutch stronghold be open. While the main part of the division was in the southern section of Rotterdam, a few daring spearheads of the parachutists had crossed both bridges and stood just north of them, at one point in the railroad station, right behind the railroad bridges north of the river, and the second point within a block of houses which was on the immediate north side of the road bridge, opposite the station and near the well-known butter or margarine factory which later played an important role. This spearhead held its position in spite of heavy and superior attacks.

I do not want to go into details here as to whether clear agreements were arrived at--examining this chronologically one can trace it down to the very minute--and whether it could be seen at all that capitulation would come about or not; this of course, for the time being concerned Rotterdam alone. At that time the group north of the two bridges was in a very precarious and difficult position. Bringing reinforcements across the two bridges was extremely difficult because they were under heavy machine gun fire. To this day I could still draw an exact picture of the situation. There was also artillery fire, so that only a few individual men, swinging from hand to hand under the bridge, were able to work their way across, in order to get out of the firing line--I still remember exactly the situation at that bridge later on.

There was no radio connection between Rotterdam and the planes. The radio connection went from Rotterdam by way of my headquarters, Air Fleet 2, to the division, from division to squadron ground station, and from there there was a radio connection to the planes. That was in May 1940, when in general the radio connection between ground station and planes was, to be sure, tolerably good but in no way to be compared with the excellent connections which were developed in the course of the war. But the main point was that Rotterdam could not communicate directly with the planes and therefore sent up the signals agreed upon, the red flares, which were understood by Groups 2 and 3, but not by group 1.

The final negotiations for capitulation, as far as I remember, took place not until about 6 o'clock in the evening. I know that, because during these surrender negotiations there was still some shooting going on and the paratroopers' general, Student, went to the window during the surrender negotiations and was shot in the head, which resulted in a brain injury. That is what I have to say about Rotterdam in explanation of the two generals and their surrender negotiations, one from within and one from without.

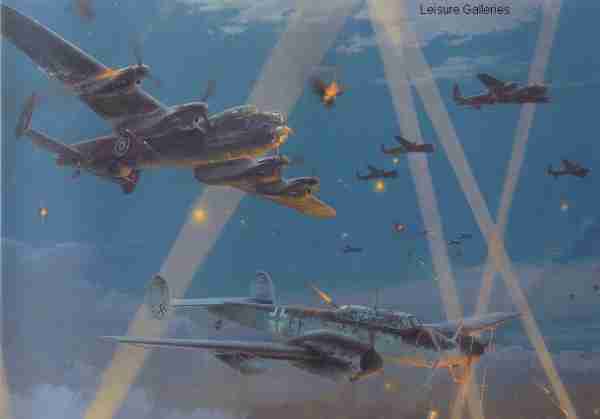

Although the Fuehrer wanted, now as before, to see London attacked, I, acting on my own initiative, made exact preparations for the target of Coventry because, according to my information, there was located in and around Coventry an important part of the aircraft and aircraft accessories industry. Birmingham and Coventry were targets of most decisive importance for me. I decided on Coventry because there the most targets could be hit within the smallest area. I prepared that attack myself with both air fleets, which regularly checked the target information--and then with the first favorable weather, that is, a moonlit night, I ordered the attack and gave directions for it to be carried out as long and as repeatedly as was necessary to achieve decisive effects on the British aircraft industry there. Then to switch to the next targets in Birmingham and to a large motor factory south of Weston, after the aircraft industry, partly near Bristol and south of London, had been attacked.

1946 Nuremberg Tribunal: On day 84, Hermann Goering is cross-examined by Justice Jackson, the chief US prosecutor.

Mr. Justice Jackson: By the time of January 1945 you also knew that you were unable to defend the German cities against the air attacks of the Allies, did you not?

Goering: Concerning the defense of German cities against Allied air attacks, I should like to describe the possibility of doing this as follows: Of itself ...

Goering: I can say that I knew that, at that time, it was not possible.

Mr. Justice Jackson: And after that time it was wen known to you that the air attacks which were continued against England could not turn the tide of war, and were designed solely to effect a prolongation of what you then knew was a hopeless conflict?

Goering: I believe you are mistaken. After January 1945 there were no more attacks on England, except perhaps a few single planes, because at that time I needed all my petrol for the fighter planes for defense. If I had had bombers and oil at my disposal, then, of course, I should have continued such attacks up to the last minute as retaliation for the attacks which were being carried out on German cities, whatever our chances might have been.

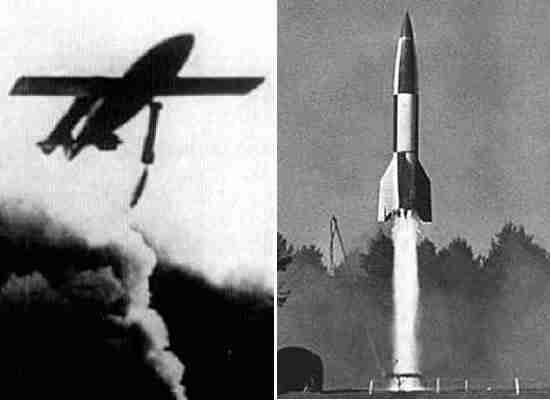

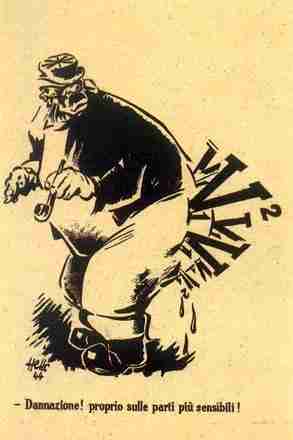

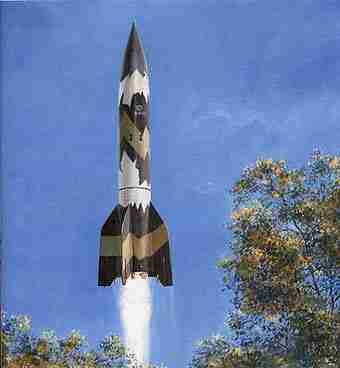

Goering: Thank God, we still had one weapon that we could use. I have just said that, as long as the fight was on, we had to hit back; and as a soldier I can only regret that we did not have enough of these V-1 and V-2 bombs, for an easing of the attacks on German cities could be brought about only if we could inflict equally heavy losses on the enemy.

Mr. Justice Jackson: And there was no way to prevent the war going on as long as Hitler was the head of the German Government, was there?

Goering: As long as Hitler was the Fuehrer of the German people, he alone decided whether the war was to go on. As long as my enemy threatens me and demands absolutely unconditional surrender, I flght to my last breath, because there is nothing left for me except perhaps a chance that in some way fate may change, even though it seems hopeless.

Goering: A revolution always changes a situation, if it succeeds. That is a foregone conclusion. The murder of Hitler at this time, say January 1945, would have brought about my succession. If the enemy had given me the same answer, that is, unconditional surrender, and had held out those terrible conditions which had been intimated, I would have continued fighting whatever the circumstances.

Mr. Justice Jackson: Well, at all events, you continued your efforts and on the 8th of November 1943, you made a speech describing those efforts to the Gauleiter in the Fuehrer building at Munich, is that right?

Goering: I do not know the exact date, but about that time I made a short speech, one of a series of speeches, to the Gauleiter about the air situation, as far as I remember, and also perhaps about the armament situation. I do not remember the words of that speech, since I was never asked about it until now; but the facts are correct.

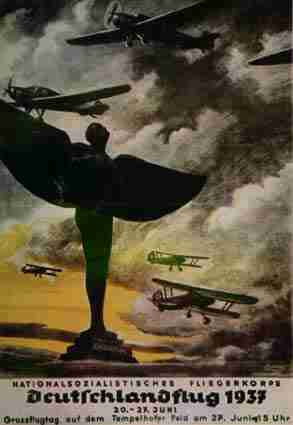

Germany, at the beginning of the war, was the only country in the world possessing an operative, fighting air force. The other countries had split their air fleets up into army and navy air fleets and considered the air arm primarily as a necessary and important auxiliary of the other branches of the forces. In consequence, they lacked the instrument which is alone capable of dealing concentrated and effective blows, namely, an operative air force. In Germany we had gone ahead on those lines from the very outset, and the main body of the Air Force was disposed in such a way that it could thrust deeply into the hostile areas with strategic effect, while a lesser portion of the air force, consisting of Stukas and, of course, fighter planes, went into action on the front line in the battlefields. You all know what wonderful results were achieved by these tactics and what superiority we attained at the very beginning of the war through this modern kind of air force.

Goering: That is entirely correct; I certainly did say that, and what is more, I acted accordingly. But in order that this be understood and interpreted correctly, I must explain briefly: In these statements I dealt with two separate opinions on air strategy, which are still being debated today and without a decision having been reached. That is to say: Should the air force form an auxiliary arm of the army and the navy and be split up, to form a constituent part of the army and the navy, or should it be a separate branch of the armed forces? I explained that for nations with a very large navy it is perhaps understandable that such a division should be made.

The Nuremberg Tribunal Biographies

Caution: As always, these excerpts from trial testimony should not necessarily be mistaken for fact. It should be kept in mind that they are the sometimes-desperate statements of hard-pressed defendants seeking to avoid culpability and shift responsibility from charges that, should they be found guilty, can possibly be punishable by death.

Disclaimer:The Propagander!™ includes diverse and controversial materials--such as excerpts from the writings of racists and anti-Semites--so that its readers can learn the nature and extent of hate and anti-Semitic discourse. It is our sincere belief that only the informed citizen can prevail over the ignorance of Racialist "thought." Far from approving these writings, The Propagander!™ condemns racism in all of its forms and manifestations.

Source Note: The trial portion of this material, which is available in its entirety at the outstanding Avalon and Nizkor sites, is being presented here in a catagorized form for ease of study and is not meant to supplant or replace these highly recommended sources.

Fair Use Notice: This site--The Propagander!™--may contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of historical, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, environmental, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a "fair use" of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.